N.S. farm family boasts state-of-the-art egg laying operation

/by Dan Woolley

A fourth-generation farming family operates what could be the most modern and technically sophisticated egg laying operation in Atlantic Canada – Seaview Poultry Ltd. on the Starrs Point Road just outside of Port Williams in Nova Scotia’s Kings County.

The Cox family partnership includes Tim Cox, his brother Warren, and their parents Chris and Susan.

In 2000, the Cox family exited the hog industry, not seeing any future in it, and entered into broiler production.

Two years later, the family bought the first egg quota Maple Leaf Foods sold off in 2002, plus the Maple Leaf poultry barn next to their farm, when the company pulled back from the Annapolis Valley poultry industry.

“I have been managing the layers since we bought the egg quota,” said Tim. “Around 2005, we bought into the Maritime Pride egg grading station in Amherst. My brother Warren is the president of Maritime Pride and chairman of its board of directors.”

On the broiler side of the Seaview Poultry enterprise, Warren and Tim have separate businesses, but the egg operation is jointly owned.

Tim continued, “In 2013, we added about one-third more production when we bought out another egg operator and built our first enriched egg production facility.”

His mother does Seaview’s bookkeeping while his father and brother raise crops on the farm’s 600 acres sown in corn, soybeans, and Winter wheat in rotation to feed Seaview’s poultry flock. Tim’s father also has a 20-head hobby herd of Simmental, Charolais, and Black Angus beef cattle.

NEW REGULATIONS

“In early 2019, we started building our second enriched barn. That was because of the new regulations that came in that would not allow us to house at less than 116.25 square inches per bird,” Tim said.

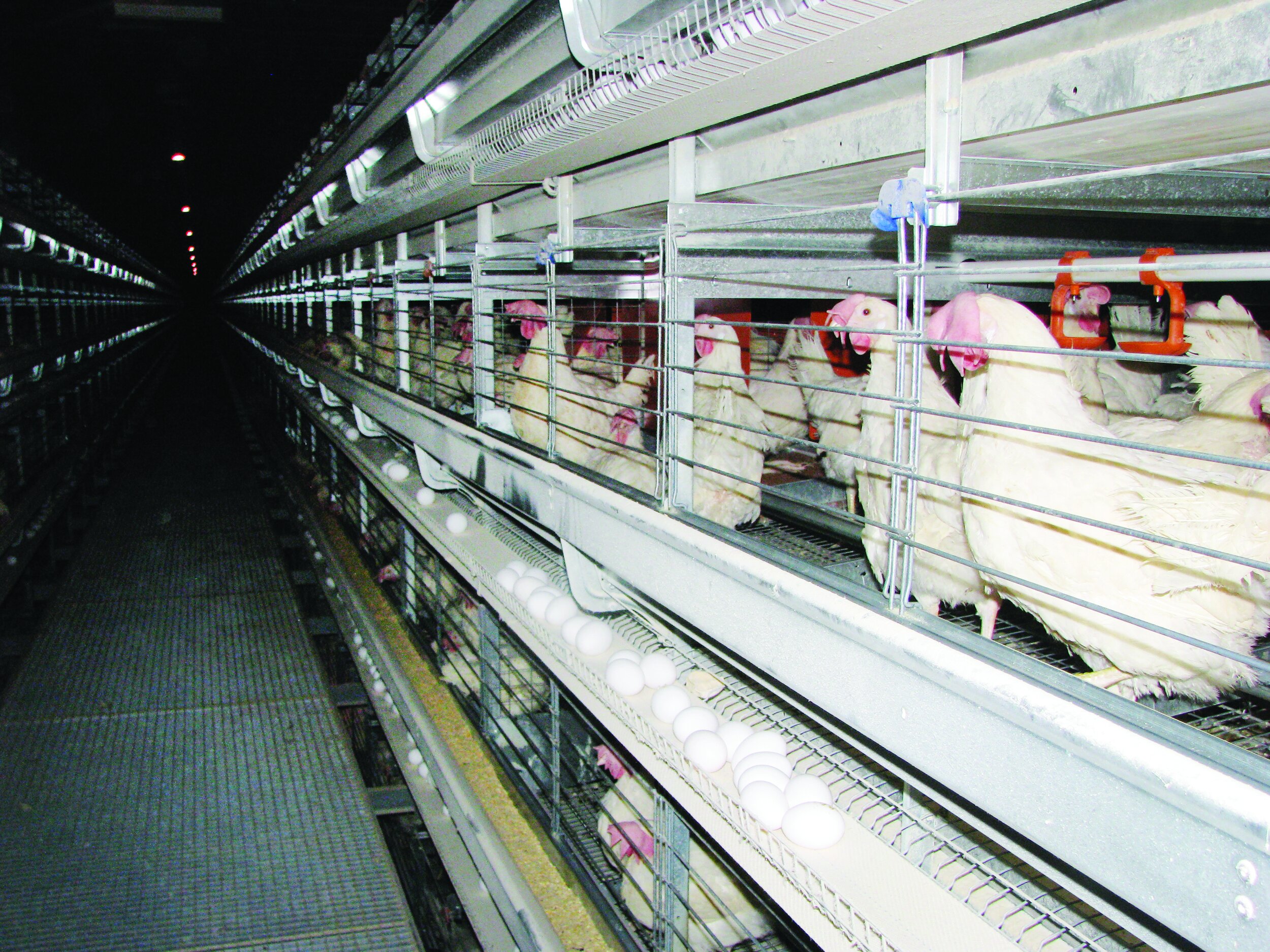

The enriched cages have perches for the hens and there’s a curtained area in their housing where they can lay their eggs.

When the Cox family built their two enriched layer barns, they installed computer-controlled systems for internal environmental conditions and egg production flow management from Poultry Management Systems Inc. of Michigan. Tim remarked, “It is so nice to work in here in the summer when it is 34 degrees outside that people don’t mind coming to work here.”

Besides computer control of the barn temperature, the egg flow from the layers’ housing is regulated to the egg packer, which packs and stacks eggs at the end of the main conveyor belt. Another innovation Tim likes is the “dim-to-red” lighting. “That really helps with the production and calms the birds down,” he said.

He also noted, “We spent a lot of money on ventilation. To get the most out of the flock, you need a consistent temperature in the barn.”

Tim also acknowledged the necessity in recent years to change their management procedures and protocols. “There are a lot more animal welfare audits and paperwork required,” he said. “The marketplace demands it.”

He added that during the past 10 years, Seaview has had “pretty good organic growth” due to quota expansion responding to market demand.

Currently, Seaview has 56,000 layers producing 53,000 eggs daily. His broiler business, which he owns jointly with his wife Lissa, produces 850,000 kilograms of chicken annually.

ENRICHED HOUSING

Seaview’s second enriched cage housing system went into production in April 2020.

The layers in the new enriched barn are housed in four 225-foot-long cage rows, five feet wide and six tiers high. There are horizontal conveyor belts along the side of each cage row that carry away eggs as they are laid, depositing them into two vertical elevator belts which then place the eggs onto another conveyor belt that sends them to the Moba egg packer and tray stacker.

Seaview’s state-of-the art layer housing has attracted a lot of attention from those interested in the poultry industry. Tim regularly hosts group tours of his new egg processing production facility. He has had accountants, bankers, and politicians on the premises.

“All of them are really shocked at how well the conditions are in the barn,” he said.

Tim has also hosted groups of his fellow poultry producers. He believes everybody in the egg laying industry will have to eventually transition to enriched layer housing. “Farmers are blown away by all the automation in here,” he said.

Every 13 months, he changes out his layer flock. Jeff and Kelly Clarke, fellow Annapolis Valley poultry producers, grow the Cox family’s replacement pullets and also mill their feed.

The Cox family operate their Seaview Poultry farm with five employees.

Along with all other Canadian poultry farmers, they face increased foreign competition in the domestic marketplace.

On Nov. 28, the federal government announced $691 million in compensation for Canadian poultry producers for their loss of domestic market share resulting from the CETA and CPTPP trade deals.

According to the federal government, the $691 million will be used “for 10-year programs for Canada’s 4,800 chicken, egg, broiler hatching egg, and turkey farmers” and the program details will be “designed in consultation with sector representatives and launched as soon as possible.”

“At the end of the day, I would much rather house birds and produce eggs for the Canadian consumer,” said Tim. “But when the government feels a need to give up market access to get a trade deal, it is important that the loss is compensated.”